Illegal diamond mining is not just an economic crime, it causes socio-economic issues as well.

Image: Pexels

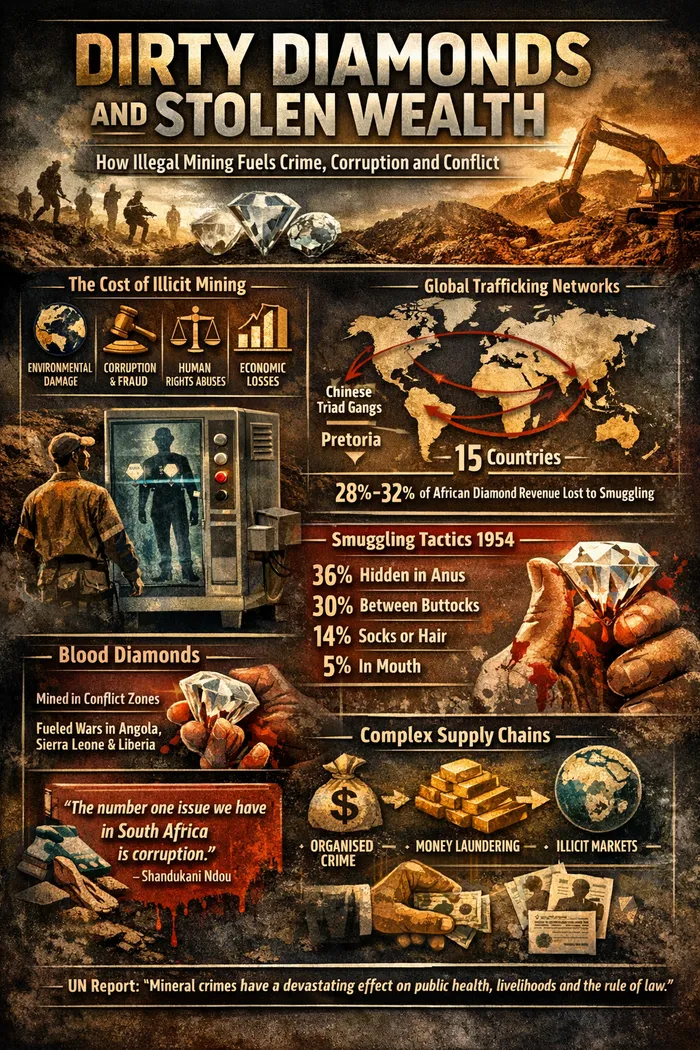

From zama-zamas to global trafficking networks, illicit precious metals continue to undermine economies, governance and security across Africa and beyond.

Illegal mining and the trafficking of precious metals continue to exact a heavy toll on peace, stability, security and development, while eroding governance, the rule of law, environmental protection and economic growth.

In South Africa, zama-zama syndicates target both abandoned and active mining operations, particularly in the Northern Cape and Namaqualand. Their activities result in substantial financial losses for the state and for legitimate mining companies, while feeding a broader criminal ecosystem.

Global networks, local bases

The problem extends far beyond informal miners. Research firm IDEX has stated that Chinese Triad gangs use Pretoria as a base to co-ordinate a global diamond trafficking network spanning four continents and involving 15 countries.

The scale of the losses is stark. The African Diamond Council has estimated that between 28% and 32% of total revenue from African diamond production is lost through the smuggling of unpolished stones.

According to the United Nations, illegal mining of precious metals is frequently accompanied by serious human rights abuses and severe environmental damage, including deforestation, land degradation and pollution.

The organisation has also warned that illicit mining and trafficking are often linked to economic crimes such as tax evasion, fraud and corruption, enabled by loopholes in regulatory frameworks.

“Due to the high profits associated with precious metals, and the often-low risks of being arrested or prosecuted, organised criminal groups are exploiting this sector,” the UN has noted.

A long history of smuggling

Diamond smuggling is far from a modern phenomenon. A Facebook post published last month by the History Timeline group traces the practice back to at least 1954, when workers leaving De Beers diamond mines in South Africa were X-rayed at the end of every shift.

At the time, fluoroscopes were used to produce real-time X-ray images to detect diamonds being smuggled out of the mines. History Timeline noted that smuggling was surprisingly common, citing a report from a Botswana mine that detailed the various concealment methods used by workers.

A separate post by Ancient Hippocrates earlier in January added context, noting that fluoroscopy at the time offered minimal radiation protection, as the long-term dangers of X-ray exposure were not yet fully understood.

Diamond smuggling in numbers.

Image: ChatGPT

Africa’s mineral wealth and its risks

An undated statement from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime notes that about half of the world’s vanadium, platinum and diamonds are sourced from sub-Saharan Africa, according to the Southern African Development Community.

“A lot of these countries’ economies are dependent on income generated from these minerals,” said Coleen Yisa, senior public prosecutor in the Office of the Prosecutor General of Namibia.

That dependence, however, also creates vulnerability. The UN has warned that the outsized role of mining in the Southern African economy exposes countries to minerals-related crime, with impacts that extend far beyond mine sites.

“Mineral crimes have a devastating effect on public health, livelihoods, the environment and the rule of law,” Yisa said.

Complex, opaque supply chains

The supply chains for precious metals and minerals are highly complex and often opaque, making them particularly vulnerable to organised crime and corruption. The UN’s Global Analysis on Crimes that Affect the Environment found that growing global demand for minerals only amplifies these risks.

In parts of Africa, organised crime groups use mining profits to fund armed activity, consolidate territorial control and fuel conflict.

Corporations and individuals involved in these crimes, the report found, frequently rely on fraud, corruption and money laundering to move illegally sourced minerals into legitimate global markets.

One of the most notorious examples was the trade in so-called blood diamonds, mined in war zones and sold to finance armed conflict in Angola, Sierra Leone and Liberia during the 1990s.

From outrage to regulation

International attention intensified after Global Witness published its 1998 report, A Rough Trade, which exposed the role of diamonds in funding conflict. The resulting outcry led to the establishment of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme in 2003.

The Kimberley Process brought together governments, the diamond industry and civil society to introduce controls on the export and import of rough diamonds, with the aim of preventing the financing of violent insurrections.

From January 2003, participating countries were required to certify all shipments of rough diamonds.

Illegal diamond miners - zama zamas- in action.

Image: Wikimedia

Further efforts followed. In 2019, the UN Economic and Social Council adopted a resolution on combating transnational organised crime and its links to illicit trafficking in precious metals and illegal mining.

The measure sought to enhance the security of precious-metal supply chains, based on recommendations from the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice.

The resolution raised concerns about the growing involvement of organised criminal groups and the expanding volume and range of transnational offences linked to illegal mining and trafficking.

It called on states to strengthen cooperation with UN agencies and international partners, improve law-enforcement and prosecutorial capacity, and make better use of data and technology.

Legal diamond mining at the Petra-owned Cullinan mine north of Pretoria. It is at this mine where the magnificent Cullinan Diamond – the largest diamond ever found - was mined. The stone is incorporated into the Crown Jewels.

Image: Petra Diamonds

Corruption remains central

Despite these measures, the problem persists. In an undated UN statement, Shandukani Maureen Ndou, a diamond and precious metals regulator in South Africa, said “the number one issue we have in South Africa is corruption – especially in the mining industry”.

The UN has found that some actors exploit legal loopholes and weak oversight to obscure the origins of minerals, while others bribe officials to secure concessions, avoid penalties, or forge permits and documentation.

The consequences continue to surface at street level. Just a year ago, IOL reported that Western Cape police arrested three suspects allegedly caught attempting to sell uncut diamonds in Cape Town. Officers seized a diamond tester and stones with an estimated value of about R60,000.

IOL BUSINESS