South Africa’s poorest need only R855 a month to get by, Stats SA says

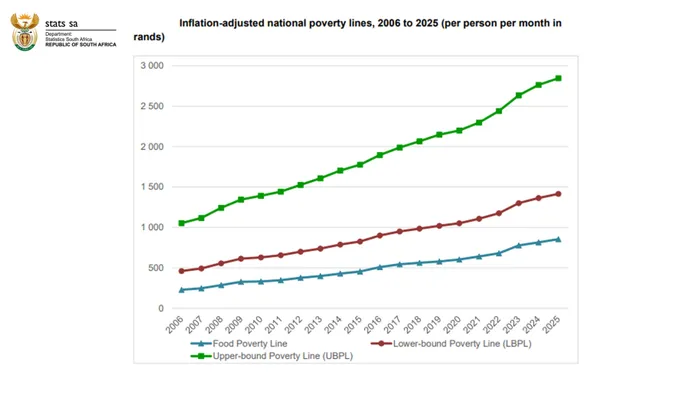

Two decades ago, the upper-bound poverty line was measured at R1,054, while the food poverty line was a mere R228 a month.

Image: Pixabay

Statistics South Africa’s revised poverty line shows that the upper band, at R2,846 per month, earns just enough to cover basic food, household staples and essential items.

At the bottom end, the food poverty line is only R855 a month, barely enough for the minimum daily energy intake.

This comes as the national statistics agency publishes its 2025 poverty line update, based on the latest household expenditure data.

Statistics South Africa said the updated benchmarks track the money households need for food and essential goods, giving a picture of who is just scraping by and who isn’t.

The food poverty line measures the minimum required to meet daily energy needs, while the lower- and upper-bound poverty lines include additional non-food essentials.

Combined, they offer a clearer view of living conditions across different households and income groups, showing how far money stretches for families across the country.

These “lines” are now:

- Food poverty line – R855 (in May 2025 prices) per person per month. This refers to the amount of money that an individual will need to afford the minimum required daily energy intake. This is also commonly referred to as the “extreme” poverty line;

- Lower-bound poverty line – R1,415 (in May 2025 prices) per person per month. This refers to the food poverty line plus the average amount derived from non-food items of households whose total expenditure is equal (or near) to the food poverty line; and

- Upper-bound poverty line – R2,846 (in May 2025 prices) per person per month. This refers to the food poverty line plus the average amount derived from non-food items of households whose food expenditure is equal (or near) to the food poverty line.

The latest update draws on the 2022/23 Income and Expenditure Survey and May 2025 prices.

However, it does draw a bleak picture. Taking the upper-bound poverty line, this works out to spending “power” of:

Staples

- 10 kg maize meal: R180

- 2 kg rice: R70

- 2 kg pasta: R40

- 2 kg sugar: R40

- 2 litres cooking oil: R60

Proteins

- 2 kg chicken portions: R180

- 1 kg beef mince: R150

- 6 eggs: R30

Dairy

- 2 litres milk: R60

- 250 g cheese: R60

Fruit & vegetables

- 1 kg potatoes: R40

- 1 kg onions: R30

- 1 kg tomatoes: R50

- 1 kg apples: R40

- 1 kg oranges: R40

Other essentials

- 1 loaf of bread: R25

- Tea/coffee: R50

- Toilet paper, soap, cleaning: ~R100

Subtotal: ~R1,205

That leaves roughly R1,600 for other monthly essentials — transport, electricity, water, airtime, medical needs, school fees, and other non-food items.

The poverty lines according to Statistics South Africa over 20 years.

Image: Statistics South Africa

So even at the upper-bound poverty line, there’s enough to cover basic food and some essentials, but not much room for savings, emergencies, or discretionary spending. It really shows why these lines are more about survival budgets than comfortable living.

Contrasted with the statutory national minimum wage of R30.23 per ordinary hour worked, which works out to R5,230 a month, this is 1.8 times what the upper-band of the poverty line earns.

This translates into a full-time worker on minimum wage earning almost twice what is considered enough to cover basic food and essential needs.

Two decades ago, the upper-bound poverty line was measured at R1,054, while the food poverty line was a mere R228 a month.

Using the internationally recognised Cost of Basic Needs approach, Statistics South Africa calculates the lines by linking welfare to actual household consumption patterns. This ensures the measures reflect real-life spending, not just theoretical budgets.

The poverty line series was first introduced in 2012 and rebased in 2015. The 2025 update incorporates the latest household expenditure data and was developed in partnership with the World Bank.

Statistics South Africa says regular revisions are vital to maintain the relevance of the lines over time, particularly as living costs shift.

The update also reflects changes in how households spend their money, including both essentials like food and housing, as well as other necessary items such as clothing, transport, and basic services.

By accounting for these patterns, the poverty lines provide a benchmark not just for policy-makers, but also for researchers and organisations tracking socio-economic trends across South Africa.

Statistics South Africa emphasises that while the lines indicate minimum income needs, they do not measure wealth or overall quality of life. Instead, they are a tool to understand economic vulnerability and monitor shifts in household welfare across the country.

IOL

Related Topics: