How AI can revolutionise rural development in SA

Opinion

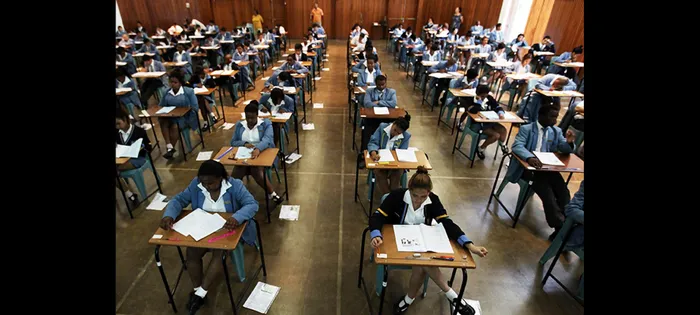

Grade 12 pupils in KwaZulu-Natal. As South African learners approach their matric examinations, the nation is forced to confront a recurring national paradox.

Image: Supplied

AS NEARLY a million South African learners approach their matric examinations, the nation is forced to confront a recurring national paradox.

South Africa holds a unique position on the global stage as the only African nation which is a member of the G20 and the first African nation to be co-opted into the foundational BRICS nations.

This status, however, stands in stark contrast to its domestic reality. South Africa holds the highest rates of public investment in education, but consistently produces education outcomes that rank among the world’s poorest.

An entire generation needs to be urgently reoriented towards future-facing skills. Our nation is simply not technologically ready or equipped for a world where the nature of work is being transformed beyond traditional models of dependency.

This failure is most acutely felt in rural areas, where geographical isolation and resource scarcity intensify the crisis. For decades, policy has focused on essential but insufficient goals like building more schools and hiring more teachers, 20th-century solutions for a 21st-century problem. This approach has failed to keep pace with a rapidly evolving global economy.

South Africa has to find viable solutions that match the magnitude of its challenges, and the G20 summit provides a critical platform for this. As a member, the country has a unique opportunity to move beyond symbolic diplomacy and actively learn from a fellow member nation that has turned a similar crisis into an opportunity: India.

India’s strategic and practical deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) to address its own developmental challenges offers a powerful blueprint.

India’s transformative journey began with a strategic vision. The formal launch of the #AIForAll strategy in 2018 was a deliberate decision to harness Artificial Intelligence not as a luxury for the elite, but as a practical tool for mass upliftment.

The government, in partnership with its world-class tech industry, chose to focus AI development on “high-impact sectors” where it could bridge critical gaps: healthcare, agriculture, and education.

This was a strategic masterstroke. Instead of waiting to build thousands of new clinics and schools in every remote village, India began building digital bridges. The question shifted from “How do we get a doctor to every village?” to “How can we get medical expertise to every village, instantly?”

The results have been tangible. In education, India is deploying AI to overcome its immense linguistic and resource diversity. Platforms act as personalised tutors, capable of teaching a student in their mother tongue, adapting to their learning pace, and identifying knowledge gaps early. This is crucial in a country with 22 official languages, much like South Africa’s own linguistic landscape.

In healthcare, the impact is dramatic. AI-powered applications used by community health workers can analyse symptoms from a simple description or image to provide preliminary diagnoses. This extends the reach of a limited number of doctors to millions in rural areas, ensuring faster interventions and better health outcomes.

The stark reality, highlighted in a recent Moneyweb report, is that most South Africans have little to no interaction with AI. It is perceived as a distant technology for elites, not a tool for solving everyday problems in Soweto, Khayelitsha, or rural villages.

This stagnation is acutely felt by millions of young people in rural areas, for whom the digital divide cuts off any prospect of meaningful participation. The critical issue is the gap between theory and practice. Even where technology is introduced in South Africa, it is often a theoretical subject, not an integrated tool for problem-solving.

If AI remains an abstract concept, it will never drive the change we need. The question is not whether we can afford to invest in AI education, but whether we can afford the catastrophic cost of inaction, a generation left behind, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality.

India’s success stems from a deliberate national strategy to democratise technology. Their approach is a masterclass in practical application, centred on key pillars from which South Africa can learn:

- A Clear, Inclusive National Strategy: India’s #AIForAll strategy prioritises sectors where AI can have the greatest social impact. The goal is tangible improvement in the quality of life for its citizens.

- Grassroots Problem-Solving: India’s tech revolution addresses foundational challenges. AI-powered apps like Swasth AI provide healthcare diagnostics in local languages, while platforms like Plantix help farmers diagnose crop diseases via smartphone.

- Integrating AI into the Educational DNA: India’s National Education Policy 2020 embeds computational thinking and coding from the school level, fostering a culture of creation.

The Indian model offers a blueprint, but our solution must be uniquely South African. We must ask: What does AI for South Africa look like? How can we make it practical for our townships, villages, and cities?

The path forward has been mapped by nations that have faced similar odds. India’s journey in leveraging AI for grassroots service delivery is a powerful lesson in South-South cooperation, demonstrating that with strategic vision, technology can become the great equaliser.

For South Africa, this presents a historic opportunity to redefine development by adopting a rural-youth first AI strategy.

The potential is transformative. Imagine AI-powered mobile clinics bringing diagnostic capabilities to remote villages, bridging the healthcare gap that has persisted for generations. Envision digital learning platforms delivering quality education in local languages to students in under-resourced schools, ensuring that a child’s potential is not limited by their geographic location.

This is not a distant dream but an achievable reality, capable of turning rural areas from zones of exclusion into hubs of innovation and productivity.

As the first African country to host the G20, South Africa has a unique platform to champion this inclusive model. The solution lies not in increasing expenditure on outdated systems, but in radically reorienting our strategy to emulate proven, practical approaches.

By prioritising the integration of AI into rural health and education, we can empower our youth, our greatest asset, with the tools to become innovators and problem-solvers.

This is how we break the cycle of dependency and build a self-reliant, industrious citizenry prepared for the economy of tomorrow. The time for a youth-focused technological leap is now.

* Phapano Phasha is the chairperson of The Centre for Alternative Political and Economic Thought.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, IOL, or Independent Media.