Trump's Tariffs Must Sow the Seeds for a National Reawakening

TRUMP'S TRADE WARS

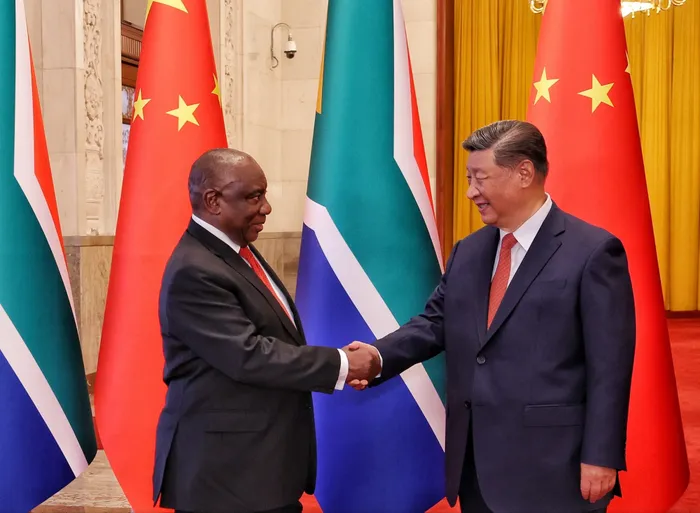

President Cyril Ramaphosa and his Chinese counterpart President Xi Jinping. China must be persuaded to localise the manufacturing of its automotive brands in South Africa. This is not a charity request; it is a strategic proposal, says the writer.

Image: GCIS

Zamikhaya Maseti

On August 1, 2025, South Africa will enter a zone of strategic economic pain, engineered not by global market fluctuations, but by the vengeful hands of conservative economic nationalism.

The United States, under the reins of Donald J. Trump, will impose a 30 per cent tariff on all goods and products exported from South Africa to the American markets. This is not a policy of trade readjustment; it is a geoeconomic act of hostility. The justification, wrapped in the language of "reciprocity," is in reality a strategic blow aimed at disciplining South Africa’s geopolitical posture and diplomatic boldness.

Trump’s economic nationalism, which sits at the ideological centre of Conservative Republicanism, is not merely inward-looking. It is punitive, retaliatory, and profoundly regressive. It has shaken the global trade architecture, not to recalibrate it, but to bend it in favour of America's new mercantilist order.

This doctrine does not merely target trade imbalances; it punishes defiance. South Africa is now paying the price for standing on principle, particularly for its posture on Palestine and its landmark case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. It is clear, painfully so, that South Africa is being economically strangled not for what it trades, but for what it believes.

Some Western analysts, ever keen to defend the status quo, will dispute this. They will search for economic rationality in an act that is blatantly political. Let them continue their intellectual gymnastics. This moment calls for clarity, not politeness.

The truth is that Trump’s worldview is transactional and tribal, and in that logic, South Africa has become collateral. That South Africa is seen as an irritant in Washington’s new world order is not coincidental; it is structural. And let it be said without fear, Trump’s policy on South Africa is influenced not only by economic calculations but by the mythologies peddled by actors like AfriForum and Elon Musk, who have exported the lie of white genocide into America’s political bloodstream.

But this is not the time for victimhood, nor is it the moment for diplomatic lamentation. It is time for South Africa to do some difficult thinking and embrace a new, muscular pragmatism. Diplomatic efforts, however noble, are unlikely to change Trump’s position.

Minister Parks Tau and his diplomatic team may work tirelessly, but they are facing a political machine that does not respond to nuance. Trump’s narrative is fixed, and in that narrative, South Africa is an unfriendly trading partner whose tariffs harm American interests.

He argues, correctly or not, that South African import duties and market access protocols are unfavourable to US goods. That argument, however flawed, resonates with his domestic base, and therefore it will stand. The United States will not blink, and it will not backtrack. Thus, it is not sufficient for South Africa to hope against hope; it must respond.

Minister Parks Tau, trade envoys, and industrial leaders must now do the hard intellectual and strategic labour of repositioning the country’s economic posture. Nowhere is this urgency more pressing than in the automotive sector, a critical node of South Africa’s manufacturing ecosystem.

This sector is not only a source of direct jobs; it sustains a complex web of downstream industries, from component manufacturing and logistics to retail and after-market services. It is here that the 30 per cent tariff will hit hardest, and it is here that innovation, not inertia, must be summoned.

The sector must accept that the American market, for the foreseeable future, has lost ground. The time has come for South Africa to pivot decisively toward other markets, especially those aligned with its economic diplomacy ambitions.

The first option lies in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the single largest integrated market on the continent, and the largest globally by number of countries. With over 1.3 billion people and a combined GDP exceeding $3.4 trillion, the AfCFTA offers South Africa a natural and politically friendly trading space.

Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, presents high-value demand for affordable, durable automotive products, especially among its emerging middle classes and youthful populations. Research shows that more than 60 per cent of the region’s population is under the age of 25, representing a long-term demand curve that is not speculative, but empirically grounded.

Yet, South African companies have been slow to leverage this opportunity. There remains an unhealthy fog of Afro-pessimism and the lingering delusion of South African exceptionalism. These intellectual blindfolds must be cast aside. Africa is not a dumping ground; it is a destination for growth.

The automotive industry must shift from waiting for trade to come to it and instead begin creating strategic partnerships in East, West, and Central Africa. This includes setting up joint ventures, service hubs, and low-cost satellite assembly plants across regional economic communities.

The second and equally strategic option lies in a new industrial partnership with China. The presence and popularity of Chinese-made vehicles in the South African domestic market has reached a saturation point. They are competitively priced, technologically competent, and now represent a serious challenge to traditional brands. But if left unmanaged, this trend could lead to the hollowing out of South Africa’s manufacturing base.

South Africa must use its BRICS membership as a strategic lever. China must be persuaded to localise the manufacturing of its automotive brands in South Africa. This is not a charity request; it is a strategic proposal. Chinese companies should be invited to co-invest in high-tech manufacturing and assembly infrastructure in Eastern Cape, Gauteng, and KwaZulu-Natal.

This could take the form of co-assembled production alongside legacy OEMs like Mercedes-Benz SA, which now face looming layoffs. The South African government must incentivise this localisation through targeted industrial policy, special economic zones, and technology-sharing frameworks.

In this regard, the principle of “South Africa Inc” must be revived with urgency. Under President Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa Inc refers to the coordinated use of economic diplomacy, government strategy, and business networks to advance national economic interests abroad. Its objectives are to integrate South African companies into key markets, attract strategic investment, and drive regional industrialisation.

In Southern Africa, this approach has already delivered notable success, such as increased South African corporate presence in Zambia, Namibia, and Mozambique, particularly in retail, finance, and energy sectors.

Now is the time to bring the automotive sector under this umbrella. South African diplomatic missions across Africa and Asia must be tasked explicitly with facilitating market entry, assembling policy frameworks, and brokering industrial partnerships for local manufacturers. This is not merely export promotion; it is the safeguarding of South Africa’s industrial sovereignty.

In conclusion, the Trump tariffs should not be seen as the end of a trade relationship, but as the beginning of a deeper national reawakening. The South African government must retool its economic diplomacy, its industrial incentives, and its regional vision.

The automotive sector, in particular, must abandon old comfort zones and rise to this moment with the courage of imagination and the rigour of strategy. What is at stake is more than exports; it is the future of South Africa’s industrial identity.

* Zamikhaya Maseti is a Political Economy Analyst with a Magister Philosophiae (M. PHIL) in South African Politics and Political Economy from the University of Port Elizabeth (UPE), now known as the Nelson Mandela University (NMU).

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.