Digital public infrastructure: The need for leadership and sovereignty in South Africa’s digital future

The question of who data belongs to is a dogged question haunting national leaders of statistics formations in countries, says the author.

Image: AI Lab

The question of who data belongs to is a dogged question haunting national leaders of statistics formations in countries. Like migration of human beings, data crosses borders in more complex forms and it is the duty of the statistician-general to collate and make sense of the numerical evidence. Digital colonisation will be the battle of statisticians.

Here the statisticians have to put in place a system that enables equity in data exchange. A tough ask at that. Take for instance the International Comparisons Programme (ICP), which enables discovery in the economic sphere of countries. Participation in this transparency that enables movement of goods and services, peoples and pollutants is as complex as it comes.

The world of electronics and virtual systems is upon us. It is a world where transparency and discovery can be easy but privacy can constrain such discovery. Abuse of state power is the biggest enemy and terrifying yet abuse by factions also can harm citizenry.

Fake news is widespread, and the cases of Nkosana Makate, Eldrid Jordaan and Zakes Mda illustrate how virtual platforms can accumulate immense value. Those who sit at the top of this digital value chain often command private reserves surpassing even those of a Reserve Bank Governor. With such resources, they can buy any lawyer, any judge, any priest — and certainly any politician.

Jordaan is therefore correct in arguing that, in this space, fines are ineffective. These institutions effectively print money; penalties hardly make a dent. The only meaningful tools we have are policy and regulation capable of managing their influence.

As long as their power continues to aggregate, fines will remain futile because they can easily monetize around them. It is no surprise that ten men now own $2 trillion of the world’s wealth — all concentrated in technology and luxury goods. They even extract value from the R350-per-capita SRD grant through airtime and related micro-transactions. They are sharks, swallowing everything in their path.

The statement of G20 South Africa says “Today’s inequalities are not the result of the laws of nature. They are the result of what we, as nations and the global community, have done. Inequality is a choice. It is not inevitable and can be reversed with political will.”

But who has the courage to bell not the cat but the vulture culture so rampant for decades if not centuries?

Makate’s Please Call Me Case, which has finally reached finality in a non-disclosed public account of the amounts involved in the settlement is not only an isolated case of corporate bullying but is a symptom of a global manifestation of bullying in the space of the world of electronic networks.

This also obfuscates rules of origin and the maligned arguments of the benefit of the commons. Instead in front of massive evidence expands greed and further aggregation of the commons value addition for exclusive private consumption. It was the case with Zakes Mda against Anthropic. Mda, a renowned South African novelist, was part of a class-action lawsuit against the AI company Anthropic for using his and other authors' books without permission to train its large language models. It is a similar struggle won by Ngugi waThiongo. His last publication in English was Petals of Blood. Henceforth he published in his native language until his demise a year or so ago.

These struggles against monetisation-aggregators are at the heart of undermining public good and indigenous culture and knowledge systems. Out of these skewed economic relations emerge a manmade product, which marks perpetual development failure for the South. This is where it is anchored –aggregation of the plebiscite through single point monetisation.

Six decades since the first UN Development Decade was announced, very little progress has been witnessed in Africa especially. The victories by the Davids of the South against the Goliaths of the North and their proxies, is not sporadic.

Jordaan illustrates how he threw the net over Facebook South Africa and Meta, which is the US-based company. With such muscle Jordaan stood no chance especially as Facebook wanted to engage the South African government directly when it was not a litigant in the matter. But the emissary, Facebook South Africa, of the mighty Goliath Meta, felt that there was a small fry called GovChat that could be devoured for teabreak. The two giants that operated globally argued that they were governed by international law and domestic jurisdictions were superseded by the mighty.

Perhaps a statement made by Acres Canada when it appeared before Chief Justice Lehohla in 2002 is relevant to illustrate the Northern arrogance. Acres of Canada argued that “it was unaware that its local agent was funnelling money to Sole.”

But in what was referred to as a meticulous and damning judgment, Justice Lehohla rejected this rogue agent and defence, ruling it defied common sense that the company was ignorant of the payments. He found Acres International guilty of corruption. Acres were debarred from World Bank contracts.

South Africa is hosting G20 where in Cape Town the matter of digital colonisation is to be confronted. Artificial Intelligence is but one about whose data it is? It is a battle of sovereignty. It is not a fight over Intellectual property rights and skinning and scamming the loot. It is about equality in the push for human advancement. The case of two South Africans coming from different disciplines contributing immensely to the power of technology and experience in liberating society is exemplary. Eldrid Jordaan on the Govchat vs Meta and Zakes Mda vs Anthropic are epic in the era of information technology.

As I began my book tour in Washington DC this week for The Silicon Empire vs Social Impact: The David and Goliath Battle, I was reminded how the lessons from my journey as the founder of GovChat connect directly to what the world will debate this week in Cape Town at the Global Digital Public Infrastructure Summit. When governments collaborate with the private sector to build the systems that define oursocieties, we must ensure that public interest and not private profit set the terms. Jordaan has set the parameters for the continent by virtue of precedent of GovChat’s victory over Meta and Facebook.

GovChat was designed to connect citizens directly with government. During the pandemic, it became a lifeline for millions applying for social relief grants. Yet Meta, the owner of WhatsApp, threatened to remove GovChat from its platform, putting access to vital servicesfor millions of people at risk. A single private company held the power to disconnect citizens from their government.

This is the heart of the digital public infrastructure debate. Governments across the world are building public infrastructure on private systems such as cloud services, messaging APIs and artificial intelligence. This creates new forms of dependency and vulnerability. When profit motives outweigh public purpose, the digital state risks becoming a digital colony.

If South Africa is to lead responsibly, we must begin by fixing and resourcing the State Information Technology Agency (SITA). For too long, SITA has been underfunded, constrained and reactive rather than leading our digital transformation. SITA should be the engine of state modernisation, ensuring interoperability, cybersecurity and digital inclusion across all levelsof government.

We need bold and capable leadership at SITA to drive collaboration between public institutions, startups, academia and civic innovators. Only a revitalised SITA can build the public digital rails that prevent dependency on monopolies and ensure that the data andsystems of government remain in public hands.

The Cape Town summit is an opportunity to commit to three guiding principles. First, public ownership and local governance of critical infrastructure.Second, open standards and interoperability to prevent vendor lock-in.Third, public value and citizen inclusion as the ultimate measure of success.The GovChat and Meta case was not just a South African dispute. It was a global warning. The infrastructure of democracy cannot be left to private interests. As the world gathers in Cape Town, we must decide whether digital transformation will empower citizens or enrich the few.

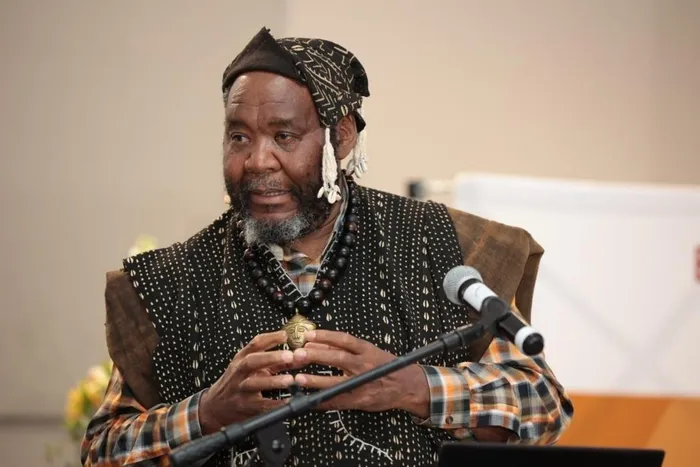

Professor Eldrid Jordaan.

Image: Supplied

Dr Pali Lehohla is a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg, among other hats.

Image: Supplied

Eldrid Jordaan is a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg. Pali Lehohla is a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg and former Statistician General of South Africa.

*** The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT