BBBEE: A deviation from Lusaka’s Vision to dismantle apartheid’s structural legacy

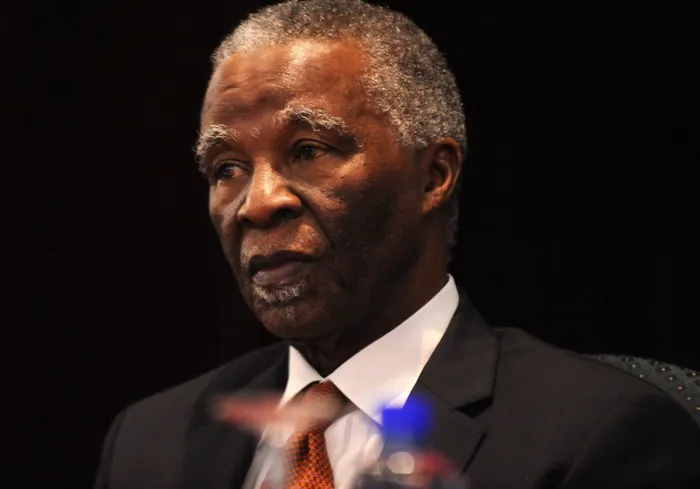

Former president Thabo Mbeki cautioned in the early 2000s against narrow-based empowerment that enriched a few rather than broadened participation.

Image: Boxer Ngwenya / Independent Newspapers

In the 1980s, ANC leaders in Lusaka envisioned a South Africa where economic justice would dismantle apartheid’s structural legacy. The 1985 Kabwe Conference called for radical redistribution to empower the black majority, denied ownership, skills and capital under apartheid. Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment, introduced in 2003, was meant to fulfil this promise. Yet in 2025, the vision falters. White households still earn five times more than black households, and South Africa’s Gini coefficient stands at 0.63, among the highest in the world. Despite three decades of black-led governance, state institutions such as the Department of Trade,Industry and Competition, the National Empowerment Fund and the BBBEE Commission have failed to shift structural inequality in a meaningful way.

Legacy white-owned companies exploit BBBEE’s opaque metrics to achieve Level 1 or 2 status through tokenism, creating an artificial parity with black startups built from struggle. The result is a distorted system inwhich genuine ownership and control by black entrepreneurs are undermined, while entrenched companies preserve their dominance under the façade of compliance.

The Lusaka-era goal was unambiguous: transfer economic power to the black majority. Kabwe rejected gradualism, calling for nationalisation and structural change. Post-1994, however, global neoliberal pressures and the Growth, Employment and Redistribution strategy reshaped empowerment into a market-driven project. Transactions worth between R150 and R285 billion disproportionately benefited politically connected elites, while most black South Africans saw little gain.

The 2003 BBBEE Act diluted the ownership pillar, reducing itto 25 points on the scorecard, while enterprise and supplier development commanded 40. This allowed legacy firms to achieve compliance without ceding meaningful control. Early empowerment share schemes demonstrated how limited participation could deliver high ratings, enriching a few while leaving ownership structures unchanged.

Even former president Thabo Mbeki cautioned in the early 2000s against narrow-based empowerment that enriched a few rather than broadened participation. Two decades later, his warning has proved prescient. Elite capture has overshadowed grassroots ownership, leaving the structural inequalities of apartheid intact.The Public Investment Corporation, custodian of R2.5 trillion, has repeatedly funded empowerment deals that entrenched elites rather than grassroots participation. Sasol’s Inzalo scheme, for example, achieved Level 2status but collapsed in 2018, leaving black shareholders with minimal control. The National Empowerment Fund has disbursed only R25 billion to black businesses by 2023, a fraction compared to the R938 billion spent annually on procurement. Meanwhile, the BBBEE Commission, constrained by budgets and political pressure, struggles to prosecute fronting and abuse.

In mining, many empowerment stakes were structured through special-purpose vehicles financed by vendor loans and external debt. Dividends serviced this debt, and when commodity cycles turned or share prices fell, debt burdens became unsustainable. As lock-in periods expired, stakes were unwound or sold down, reducing effective black ownership. Court rulings that accepted the “once empowered, always empowered” principle further allowed firms to claim continuing benefits of past deals even when black equity had diluted below thresholds. This explains why headline compliance ratings could persist while genuine ownership eroded.

The collapse of smaller black-owned financial institutions revealed governance failures, but also reinforced perceptions of uneven regulatory pressure when compared to larger legacy banks that retained favourable empowerment ratings. Among black entrepreneurs, mistrust has deepened that regulation is not applied evenly.

Similarly, the Black Industrialists Programme, expanded in 2024 to support 180 firms with R2.5 billion, cannot match the scale of established giants that secure BBBEE status without relinquishing meaningful ownership.

Budget constraints, corruption, and policy inconsistencies ensure that legacy dominance remains intact.The scorecard’s design deepens these inequities. Ownership carries only 25 points, while management control is weighted at just 15. Firms can offset weak ownership scores with enterprise and supplier development contributions. In practice, this means black startups, which achieve Level 1 through genuine ownership, cannotc ompete with corporates that tick boxes at scale.

In 2016/17, more than half of South Africa’s R938 billion procurement spend went to suppliers with undetermined black ownership, exposing how opaque systems mask exclusion.The loopholes are fertile ground for abuse. High-profile empowerment abuses in state procurement revealed how fraudulent certificates and fronting enabled companies to secure billions in contracts while bypassing genuine transformation requirements. Major logistics and infrastructure deals have similarly been tainted by practices that undermined empowerment objectives. While extreme, these cases highlight systemic vulnerabilities in verification and enforcement. Even the Minister of Finance acknowledged in 2022 that procurement corruption was undermining BBBEE’s intent.

For black startups, the barriers are crippling. Compliance costs drain SMEs, which employ more than half of black workers. Wasaa, a 100% black-owned startup that acquired a fuel terminal in 2020, lost tenders to entrenched firms despite its Level 1 status. Nala Tech, a black woman-owned startup, achieved Level 1 in 2023 but struggled with the costs of tender processes, reflecting the broader failure to meet black women ownership targets. Zuri Innovations, a youth-led renewable energy firm, faced similar exclusion in 2024 despite high ratings. SME owners increasingly view BBBEE as a tool for entrenched corruption rather than opportunity, as the National Empowerment Fund remains under-resourced.

The structural results speak for themselves. By 2020, black directorships accounted for 45% of company boards, yet only 15% of black South Africans had benefited from ownership deals. Despite decades of compliance reporting, inequality persists, and white households continue to earn five times more than black households. The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition appears more concerned with enforcing compliance than dismantling poverty and inequality. The Black Industrialists Programme remains symbolic rather than transformative, and legacy firms retain high BBBEE status without relinquishing meaningful control.

Analysts across academia, business and civil society argue that BBBEE has entrenched a narrow class of beneficiaries rather than broadening participation.

Reclaiming the Lusaka vision requires more than symbolic compliance. Ownership weighting on the scorecard must increase substantially. Procurement policies should prioritise 100% black-owned SMEs, with transparent scorecard disclosures and standardised verification to eliminate fronting. The BBBEE Commission must be properly funded and politically insulated. Compliance costs for SMEs should be reduced through tax incentives,mentorship programmes and simplified systems. Public and private partnerships must channel resources directly to black startups, ensuring that empowerment extends beyond corporate elites.

The Free Market Foundation has estimated the cost of BBBEE compliance at over R1 trillion annually, a figure that remains contested. What this number highlights is not that empowerment is wrong, but that a compliance heavy, loophole-ridden system generates enormous costs without corresponding outcomes. Administrative burdens, expensive verification, and box-ticking procurement contribute to inefficiency, while the ownership pillar, the true driver of empowerment, remains the weakest link.

At the same time, there are genuine successes, from black industrialists who have scaled firms with state support to improved representation in corporate leadership. Yet these remain exceptions in a landscape whereinequality persists. Critics and reform advocates across the spectrum agree on one point: broad-based participation must replace elite capture. South Africa cannot afford a system that equates tokenism with transformation. The promise of Lusaka was not enrichment for the few, but justice and dignity for the many. The future depends on whether BBBEE can be reformed to deliver real empowerment and dismantle the structural inequalities that persist three decades into democracy. Only by reclaiming that vision can the black majority secure its rightful place in the economy.

Nomvula Zeldah Mabuza is a Risk Governance and Compliance Specialist with extensive experience in strategic risk and industrial operations. She holds a Diploma in Business Management (Accounting) from Brunel University, UK, and is an MBA candidate at Henley Business School, South Africa.

Image: Supplied

Nomvula Zeldah Mabuza is a Risk Governance and Compliance Specialist with extensive experience in strategic risk and industrial operations. She holds a Diploma in Business Management (Accounting) from Brunel University, UK, and is an MBA candidate at Henley Business School, South Africa.

*** The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT