How to invest in China after the pandemic - Schroders

As China reopens after its extended period of Covid restrictions, how should investors approach investments in the country for a multi-asset portfolio? (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

By Michael Devereux, Multi Asset Portfolio Manager at Schroders

The question of how to invest in China has been an ongoing source of debate for multi-asset investors.

Given the major disruption to the global economy caused by the pandemic, we set out to investigate whether the future brings new opportunities, risks, or both in the context of a diversified portfolio.

Our investigations revealed five key observations, and from these we made a number of investment conclusions.

The evolution of Chinese assets

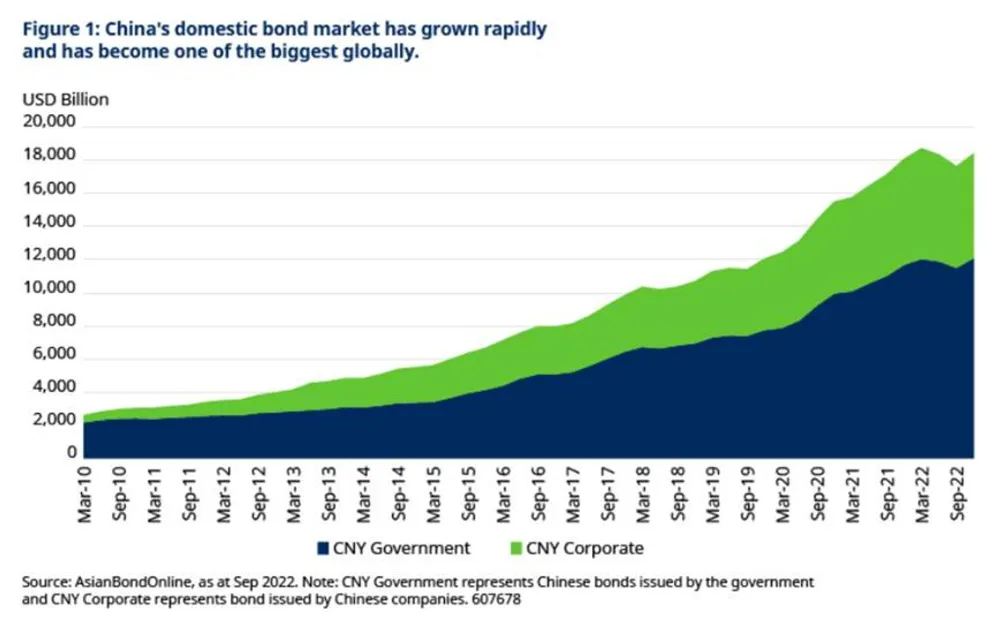

In May 2018, Chinese equities were included in the world equities index at a weight of about 3.6% (currently they are at 3.3%). Similarly, in April 2019, Chinese bonds joined the main global bond index, the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index, which means that international investors can easily gain access. China represented 6% of the $54 trillion index at the time, while the Chinese yuan (CNY) is the fourth largest currency component following the US dollar, euro and Japanese yen.

Up until recently, the main hindrance for Chinese bonds was accessibility. Now, Chinese bonds are liquid enough to be incorporated into most global indices. Chinese bonds have evolved over the years as seen in figure 1.

Our observations and views are as follows:

Observation 1: Investors outside China have low allocations to the region

Allocations to China depend heavily on where the asset owner is based. For institutional investors based in Hong Kong, there is typically a strategic allocation to Chinese equities through Hong Kong equity (i.e., offshore). For Singapore-based clients, Chinese equities are generally part of their emerging market or global equity strategic allocations. Similarly, Japanese institutions often have a World ex Japan allocation which includes China in it. Some Asian institutional investors based outside of China are starting to consider a small strategic allocation to Chinese equities. Most seem to allow additional tactical allocations to China (through onshore or offshore).

For UK-based institutional investors, many have specific allocations to emerging market equities, which incorporates an allocation to China of around 30%. The larger European institutional investors generally include Chinese equities as part of their emerging market strategic allocation and allow some additional allocation through tactical positions.

US investors generally carve out their US equity allocation separately from other equities. They then often have a strategic allocation to China through Global ex US equities or through both an allocation to Developed ex US and to emerging markets.

For bonds, most use the FTSE World Government Bond Index or Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index as their strategic bond benchmark (sometimes carving out their domestic bonds as a separate allocation) and both of these have allocations to China. Some have an Asian bond allocation as part of a broader emerging market debt strategic allocation.

Most institutional investors based outside of China have a large bias to their domestic bond market, especially where this is sizeable and liquid. As a result, Chinese bonds are likely to represent less than 3% of their current strategic allocation, and probably closer to around 1%.

Our multi-asset team’s take

A strong pick-up in domestic activity in China is expected due to its rapid reopening, and we see this as a growth driver within the region.

We think institutional investors should consider increasing their structural or tactical allocation to Chinese assets because, in the long run, we believe regulatory headwinds have peaked, new steps towards high value sectors are being made, and the government’s newly discovered ambition to stimulate the economy and shift from an investment-led to a consumer-led economy is encouraging.

Chinese assets have become liquid enough to be incorporated into the global equity and bond indices. This provides increased accessibility for investors and could potentially generate increased inflows to the country. Increased access will also be beneficial as it allows the more conservative investors to increase allocation through the offshore index which is regarded as a proxy for Chinese assets.

With more ways to gain access to this major market, we think investors should take advantage by allocating or increasing allocation to China.

Observation 2: China’s market cap significantly trails its GDP

China is the second biggest economy in the world behind the US (as measured by total GDP), but the growth of its capital markets has lagged its GDP growth. China’s low domestic capitalisation in comparison to GDP shows that the country’s stock market has not expanded as quickly as GDP.

A key factor behind this lag in growth has been the dilutive effect of IPOs in emerging markets, especially China. In our paper “Why economic growth has been a mirage for emerging market investors”, we outlined that early growth in companies happens before they IPO and the growth is captured by GDP, not by the stock market. China has seen the fastest GDP growth for any emerging market. However, it has been common practice for large state-owned enterprises to be listed on the stock market at relatively mature stages of their business cycle as a result, not capturing a lot of growth in the stock market.

Our multi-asset team’s take

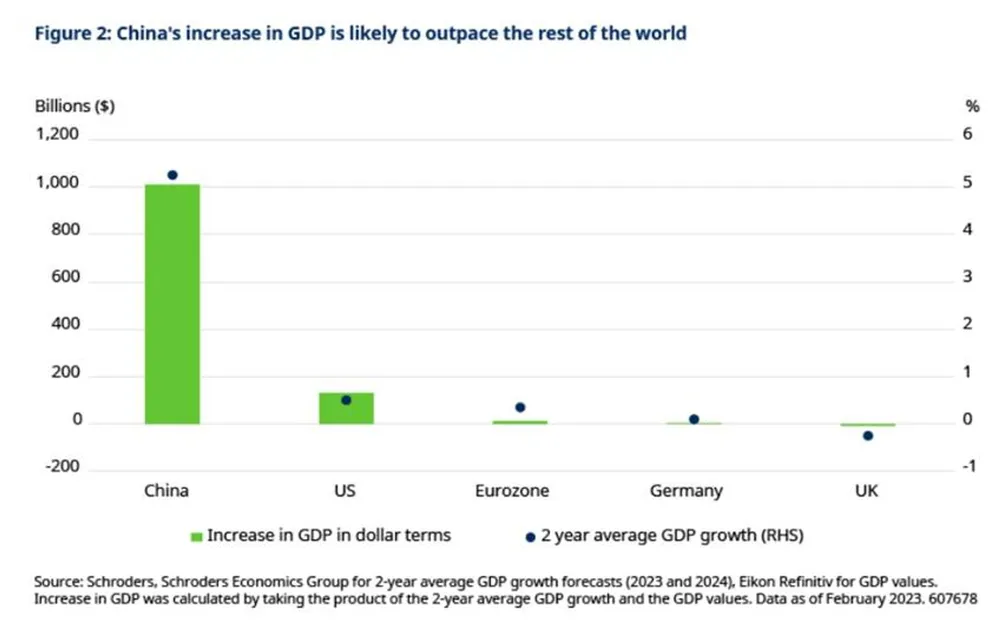

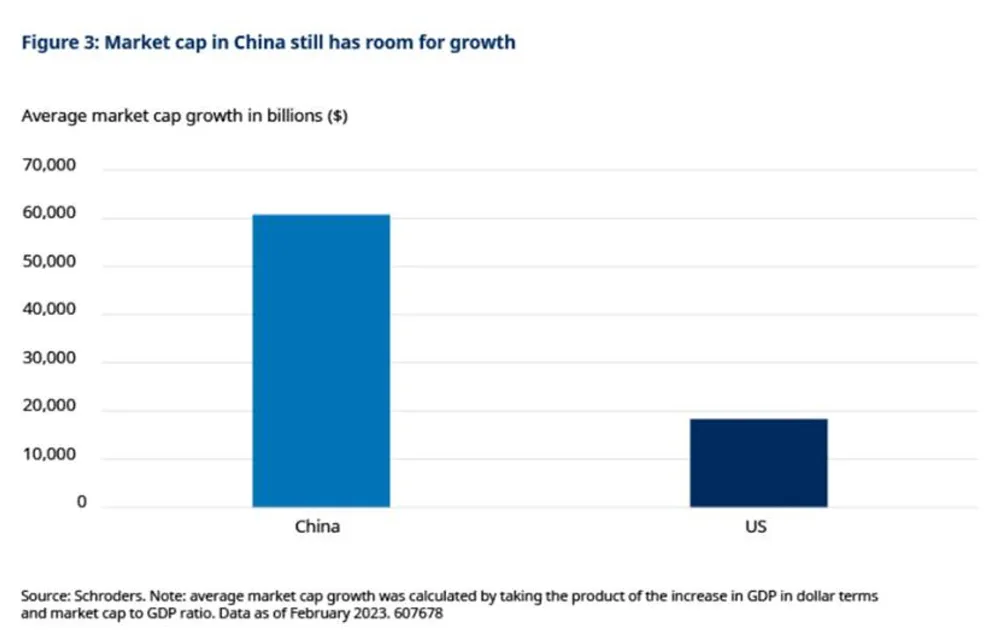

Using GDP as a valuation tool, the Chinese stock market is relatively cheap. As shown in Figure 2, using two-year average GDP growth forecasts from our economists, we calculated the increase in GDP in absolute dollar terms for various regions including China, the US, eurozone, Germany and the UK.Over the next two years, China’s GDP growth appears to be the strongest. Similarly in Figure 3, we calculated the average market cap growth over the next two years and China is likely to present better growth opportunities than its global counterparts.

This supports the case for increasing structural allocations to Chinese assets as the capital markets still have significant room for growth.

Observation 3: A global slowdown could threaten Chinese growth

Our economists believe there is a global slowdown on the horizon, but even in such an environment, China is expected to grow at a rapid pace of 4-6% over the next two years. This is as a result of the sharp turnaround from the government with regards to ending the zero-Covid policy which has created a boost in economic activity. Additionally, early indications from high frequency data and PMI surveys are that the service sectors rebounded strongly after the release of the zero-Covid policy. China is likely to experience a release of pent-up demand. There have also been efforts to increase the liquidity in the system and in turn pass on lower borrowing costs to companies in certain sectors. These factors are likely to make it easier to achieve these growth objectives.

Our multi-asset team’s take

China remains relatively resilient in the face of deteriorating external conditions. Its global counterparts are most likely facing a slowdown in growth and possible recession. Our economists are forecasting global GDP growth of 1.9% in 2023 with a slight pick-up of 2% in 2024. China on the other hand, as stated earlier, is expected to grow 4-6% in the same period. The Chinese central bank has also not been faced with the challenge of hiking interest rates aggressively. This is because domestic inflation remains benign due to the weakness that was experienced as a result of lockdowns. In the near term, China presents seemingly better growth opportunities than its global counterparts.

On the domestic demand side, since the pandemic Chinese households have amassed an excess savings of RMB3-4 trillion. This is not a huge stock of savings compared to major developed markets; however, it will contribute to a consumption rebound possibility.

So, investors must again be nimble to capture opportunities that may arise.

Observation 4: Diversification benefits through low correlation and distinct economic/policy cycles

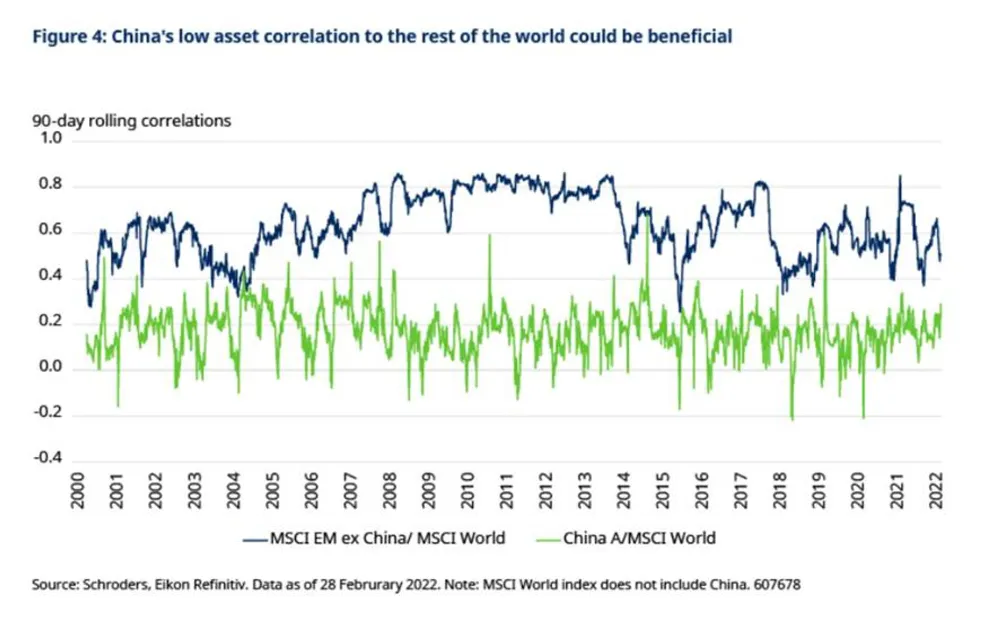

For asset allocators, onshore Chinese equities have clear diversification benefits as they have historically had lower correlation to other regions (Figure 4 below, where correlations between Onshore China and MSCI World have varied between -0.3 and 0.6) due to China’s distinct economic and policy cycles. Typically, the correlation between the Emerging Markets ex China index and the MSCI World index has varied between about 0.3 to 0.8, which is higher than China’s correlation to more developed markets (again, see figure 4).

Our multi-asset team’s take

Investing in Chinese assets is likely to be a source of diversification in multi-asset portfolios, especially with increasing opportunities to access both equity and bond markets. The low correlations to other assets could potentially provide a defensive cushion to portfolios. Although correlations are likely to increase as more foreign investors allocate funds to these assets, it is not a near-term concern.

Observation 5: Resilience in the face of deglobalization

Deglobalisation may bring challenges to China as much as to the rest of the world, but China’s increased focus on higher value sectors such as technology as well as attempts to shift to a consumer-led economy, may make it more resilient to deteriorating external conditions.

China’s quest to become increasingly more self-reliant has led it to come up with the “made in China 2025” and “Dual circulation” policies. (Made in China 2025 is an initiative which strives to make China a global leader in high tech manufacturing. Dual circulation is a policy in China that aims to make the Chinese domestic economy more balanced and resilient while reducing the role of foreign trade in driving the domestic economy. It also aims at improving the quality of trade.)

These are aimed at making the country a global leader in manufacturing and strengthening the domestic economy while growing its international importance. Although deglobalisation is likely to continue, the intertwining economic relationships may still remain, despite the narratives suggesting otherwise.

Our multi-asset team’s take

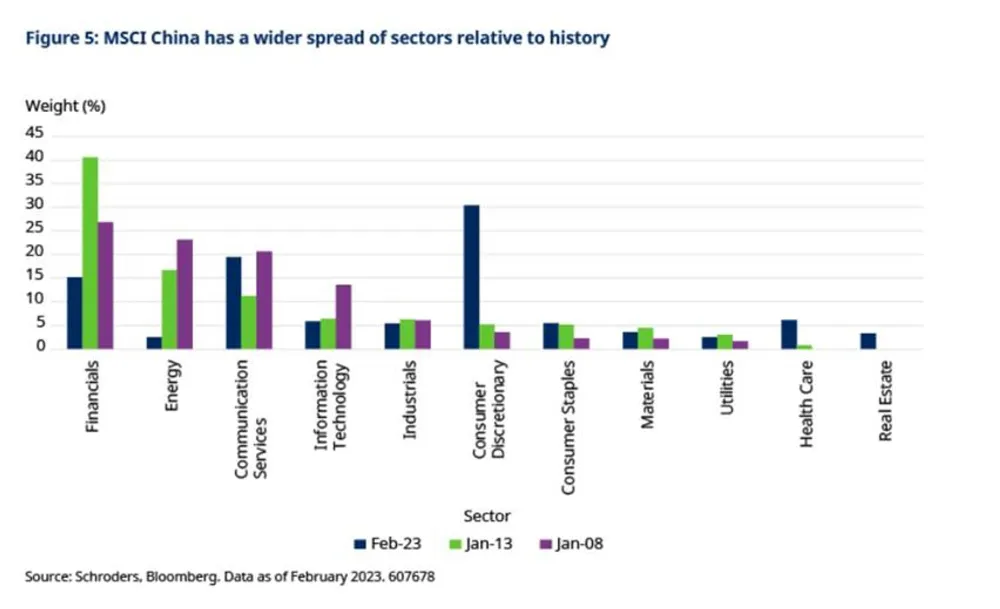

The Chinese stock market is more diversified than the economy because of the way the index is built. Its equity index now has a more balanced mix of the various sectors relative to history and continues to evolve. Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of the MSCI China index over 10-15-year period. Unlike the past, we have found that the current index composition has a broad allocation to various sectors. Additionally, the consumer discretionary and communication services sectors now comprise a significant portion of the index, which is likely to present growth opportunities for investors.

Are there near-term risks for investment into China?

As we’ve seen in other countries when they have thrown off the shackles of Covid restrictions, China’s reopening clearly brings benefits. However, the following headwinds could pose a challenge in the near term.

Slowdown in global economy: As the rest of the world slows down, this could potentially have an impact on the Chinese economy due to reduced demand for its products. Following the reversal of the zero-Covid policy, there is the potential for a significant amount of outbound tourism which may affect domestic demand. Nevertheless, from a domestic household perspective, the pent-up demand and build-up of household excess savings will likely flow into domestic services as the economy continues to pick up. The property market, once a hot-spot for investors, has peaked given controversies in recent years, but won’t cease to exist completely. From a development point of view, China has a lot of its population moving from rural areas into urban areas. The housing market will see some demand from household formation and replacement of old housing stocks. However, volumes will likely trend down over time as the population is shrinking.

Policy uncertainty and impact on specific sectors: As discussed earlier, China has distinct economic cycles due to its differing policies compared to rest of the world. Going forward, we anticipate that the government will provide support to sectors deemed strategically important as the country pushes for technological independence and growth. In other words, companies or potential listings that cannot help authorities achieve their goals and carry out national policy are likely to fall short of expectations.

Michael Devereux is a Multi Asset Portfolio Manager at Schroders

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of Independent Media or IOL.

BUSINESS REPORT

Related Topics: