The promise of SA’s pension reform depends on infrastructure investability

OPINION

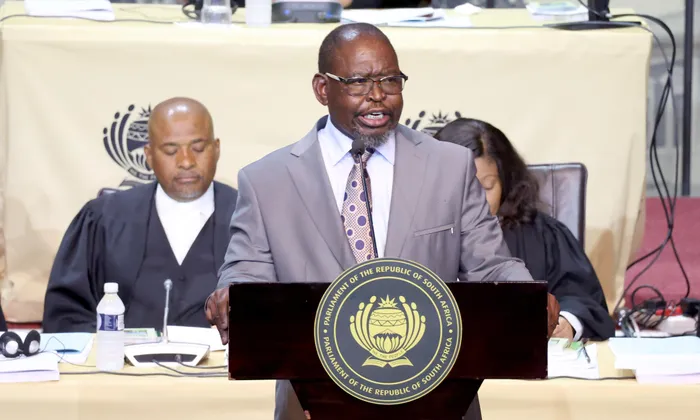

Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana did not equivocate in this year’s third iteration of the national Budget Speech: government intends to channel long-term domestic savings – particularly pension funds – towards the country’s infrastructure and industrial development priorities.

Image: Phando Jikelo / GCIS

Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana did not equivocate in this year’s third iteration of the national Budget Speech: government intends to channel long-term domestic savings – particularly pension funds – towards the country’s infrastructure and industrial development priorities.

“We are also exploring alternative financing instruments,” he said, “to allow pension funds, commercial banks, development banks and international financial institutions to participate in financing our infrastructure plans.”

The idea is not new. Proposals to more actively direct retirement savings into public interest sectors have circulated since the ANC’s 2017 policy conference, where the party raised the possibility of ‘prescribed assets’ to mobilise funding for social infrastructure.

With the introduction of the two-pot retirement system, South Africa’s R5.8 trillion pension fund industry, spanning 4 904 registered funds, is well positioned to play an even more direct role in financing national development. The reform separates savings into two components: a ‘savings pot’ allowing limited pre-retirement access, and a ‘retirement pot’ ringfenced for preservation until retirement.

By design, the system discourages early withdrawals while deepening the pool of assets held within regulated vehicles. As more funds are retained and fewer leakages occur, the size of this capital base will continue to grow, potentially unlocking a powerful domestic lever for long-term investment.

But a growing capital pool means little without a clear destination. At their foundation, pension funds must satisfy two fundamentals: diversification and yield.

They are charged with protecting retirement outcomes, ensuring that capital is not onlypreserved, but grows reliably over time. Infrastructure appears to fit this brief. It offers potential for stable, long-term returns and sits outside the volatility of listed markets.

In January 2023, regulatory amendments formally recognised infrastructure as an eligible asset class for retirement funds, permitting allocations of up to 45% across all asset classes. In principle, this opened the door to longer-term, development-aligned assets. In practice, few of these opportunities meet the thresholds institutional mandates require.

The reality is that the pipeline of bankable projects is thin and risk mitigation mechanisms are inconsistently applied. Without predictable cash flows, institutional pricing mechanisms, or efficient exit structures, infrastructure remains difficult to price, hold, and scale within highly regulated portfolios. Faced with these constraints, institutional interest in alternative asset classes has grown. Allocations into credit-based instruments and unlisted infrastructure have expanded, particularly among insurers and large retirement funds with capacity to absorb longer-dated or less liquid exposures.

Renewable energy sits at the frontier of this shift. Projects in wind, solar, and storage increasingly offer real-economy impact with attractive yield profiles, especially when structured through credit-enhanced platforms and, in some cases, blended finance vehicles.

While these allocations remain modest relative to overall portfolio size, they reflect a broader recalibration toward assets that combine income stability with tangible developmental value. There’s also the ESG consideration – particularly in South Africa, where infrastructure and inequality are deeply intertwined. But the global narrative is also evolving.

Yield has reasserted itself as the dominant concern, and the assumption that ESG and performance exist in tension is increasingly viewed as outdated. A wind farm or water treatment plant may tick every ESG box, for example, but if the return profile falls short, institutional capital cannot follow. The two must be structurally aligned.

This is the core dilemma facing asset allocators: pension funds carry explicit mandates to act in members’ financial interest. Any shift toward impact-linked allocations must meet the same standards of risk, return, and liquidity. ESG cannot be pursued in isolation from yield –and the frameworks that bridge those objectives are now among the most contested, and consequential, in the South African investment landscape.

To navigate this tension, financial institutions are developing more targeted risk-sharing and hedging mechanisms. Structured instruments such as collars, interest rate derivatives, and inflation-linked swaps are being used to align return profiles with pension fund mandates,particularly in sectors like infrastructure and renewables. These tools do not eliminate risk – but they reshape it into a form that institutional investors can underwrite.

In the local market, deal-contingent hedging and longer-dated instruments are becoming more visible, offeringfunds greater certainty in environments where volatility and tenor mismatches have traditionally limited participation. The challenge is to move from bespoke, deal-by-deal financing to a replicable investment environment capable of absorbing long-term domestic savings at scale.

South Africa’s pension reform has laid the foundation for a larger, more resilient pool of long-term capital. But scale, by itself, is not an outcome. Unless matched by an investment environment designed to receive it, the system risks building liquidity with nowhere to deploy it – or having it deployed offshore. If national development is to be financed through domestic savings, investability must be treated as a deliberate outcome of system design.

Monique Conradie, Global Head for Non-Bank Financial Institutions Coverage at Absa CIB

Image: Supplied

Monique Conradie, Global Head for Non-Bank Financial Institutions Coverage at Absa CIB.

BUSINESS REPORT